The U.S. is home to some of the most intense severe weather on the planet, and the South typically sees the worst nature can muster. Hurricanes, floods, hail, lightning and tornadoes—they’re all in the mix, and no season of the year is truly safe.

On March 24, 2023, a powerful storm system swept across the South, spawning tornadoes from Texas to Tennessee. Around 8 p.m., a tornado formed near the Mississippi River and quickly intensified to EF-4 strength as it approached Rolling Fork, Miss., where its path of destruction bisected the town.

Local sculptor Lee Washington, owner of Lee’s Cotton Picker Art gallery, was relaxing in his recliner when news of the tornado flashed across the news broadcast on his television.

“They said, ‘Rolling Fork, it looks like it's headed to you,’” Washington said. “I jumped up out of my chair, ran to the bathroom, jumped in the bathtub, and rode the storm out. While in the bathtub, I could hear the wind blowing, I could hear the windows breaking. After the storm, I called my son-in-law. That was the only way I was able to communicate with anybody. I told him to tell my wife that I was all right.”

Although it only took a few minutes to flatten much of the town with 170 mph winds, its path continued for an hour as it trekked northeast through the Delta. While residents of Rolling Fork, Midnight and Silver City scrambled in the dark to assess the damage, meteorologists were anticipating more trouble as the line of storms moved eastward.

“As the storm was forming, we knew it was bad,” said Matt Laubhan, chief meteorologist at WTVA-TV in Tupelo. “At the TV station, we were talking about how this was going to cut all the way through the state.”

How to get prepared for hurricane season

An hour after the tornado hit Rolling Fork, the same system was threatening to drop another funnel in northeastern Mississippi. Krisi Boren was watching Laubhan’s reports at her home in Amory when she and her husband decided to go to a nearby tornado shelter—one of several in the area built after an EF5 tornado devasted Smithville, just 7 miles away, in April 2011.

“We were there for about 45 minutes before the storm hit,” Boren said. “We just kept watching [WTVA] on our phones, trying to keep track of everything, and then all of a sudden, there it was. You could hear the glass breaking and the trees snapping.”

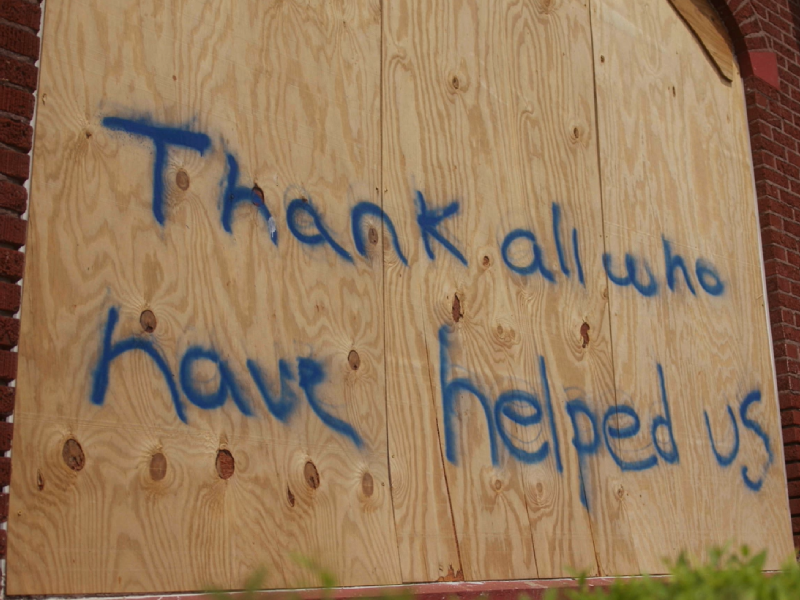

The next day, Boren was one of the many people helping their neighbors recover. She opened the food pantry at the Full Tummy Project, a non-profit she founded, and began loading supplies to deliver to kids in town. Chainsaws buzzed as people cleared the roads and homes of trees and debris.

In Rolling Fork, Washington found his small art studio wrapped around a utility pole 50 yards away, near the ruins of a water tower. His gallery fared better—it was still standing, at least—and a stranger offered to give him wood to rebuild the shop where he makes his Delta-themed sculptures out of disused cotton-picker parts.

Although unseen, another factor helped the town coordinate recovery efforts. Cellular services are crucial during and after severe-weather events, when first responders are trying to rescue people injured or trapped in debris.

C Spire wireless service remained in Rolling Fork and Silver City throughout the ordeal. Technicians rerouted 911 calls from Sharkey to Warren counties and provided hotspots and wireless routers to first responders. The company deployed a temporary tower to Amory and supplied the Monroe County Emergency Management Agency with circuitry to communicate in the aftermath.

“This is our community,” said Chandrika Turner at C Spire, a Delta resident and longtime friend of the Washington family. “These citizens are not just customers of ours; they're family, they're friends.” Storm and disaster readiness, she added, is just another way to look after each other.

“Our tower crews are always on standby and ready to assist. We stay prepared so we don't lose service in the first place.”